Breathing Room

How bad can it get and still get better?

2025-47

sermon preached at Church of the Good Shepherd, Federal Way, WA

www.goodshepherdfw.org

by the Rev. Josh Hosler, Rector

The Fourteenth Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 19C-Tr1), September 14, 2025

Jeremiah 4:11-12, 22-28 ; Psalm 14 ; 1 Timothy 1:12-17 ; Luke 15:1-10

Every day we hear terrible news. A boat blown up in international waters in a summary execution. A Fox News host suggesting a solution to homelessness: “Involuntary lethal injection. Or something. Just kill them.” An extremist with an effective facade shot and killed in front of thousands of people by an even more extreme extremist groomed by a culture of guns and revenge fantasies. A whole federal government trying to make darn sure that no matter what else happened this week, you came away with a terrifying feeling of “us versus them.”

There’s no point debating people’s relative guilt or innocence. It’s all too much right now. It’s like the walls are closing in.

Stop for a moment and breathe.

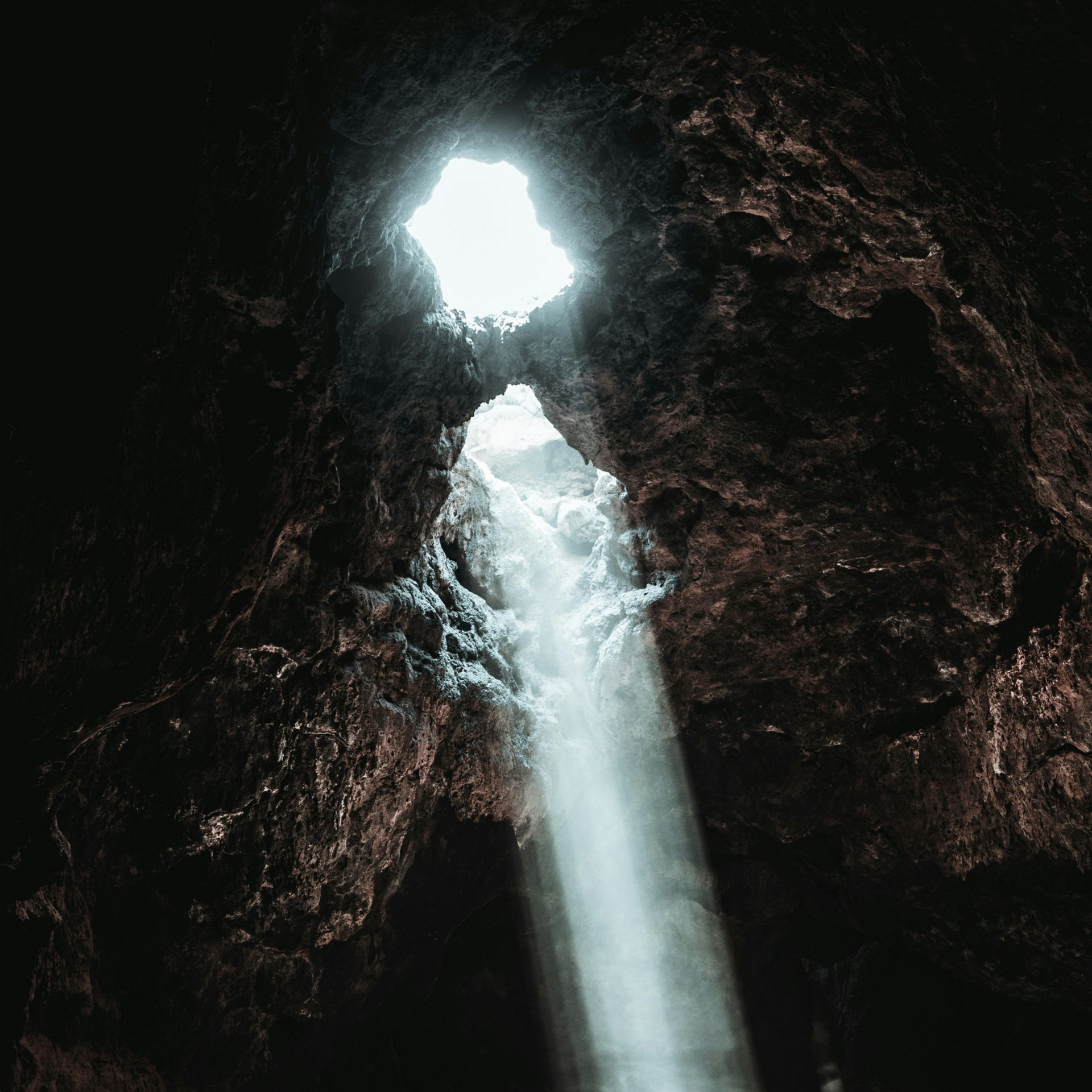

Breathe? But the air is hot and stale … like we’ve been stuck in a tight, enclosed space for a very long time. How can we find breathing room?

Well, let’s talk about breathing room for a moment. I want to pull back as far as I possibly can from all this horror and tell you a story of the creation of the universe. Is that roomy enough for you?

God sits down to paint. Got gets out the watercolors, a palette, a cup of water, paper towels. When you sit down to paint you have to make sure there’s lots of room, because it can get messy.

But where will God paint? Because at first, there’s no space for it. There is only God.

When Bishop Phil met with the vestry last week, he told us about the Jewish concept of zimzum. It’s a mystical, philosophical idea proceeding from the realization that God cannot be God’s own canvas. So to create the universe, God has to make a space—a space where God is not.

Any space where God is not is necessarily chaotic and scary. So God pulls back the very material of godself and observes the chaos—in Hebrew, it’s called tohu v’bohu. We read about it in Genesis, chapter 1, at the beginning of the whole Bible: “When God began to create the heavens and the earth, the earth was complete chaos”: tohu v’bohu.

So God creates a space in the midst of the chaos. Then God says, “Let there be light.” God turns the dark chaos into brightened order … and so we have creation.

These are the images the Prophet Jeremiah draws on today, though you might miss it if you’re not reading him in Hebrew. He writes just as the Babylonian armies are about to sweep into Judah, and he views this invasion as God’s rightful punishment for the people’s sins. Like all prophets, he speaks with God’s voice:

For my people are foolish,

they do not know me;

they are stupid children,

they have no understanding.

They are skilled in doing evil,

but do not know how to do good.

What will God do about it? What will be the consequence? Jeremiah has a vision:

I looked on the earth, and lo, it was waste and void;

and to the heavens, and they had no light.

Look at that language in Hebrew! Waste and void? That’s tohu v’bohu … total chaos in the space that God had once cleared out for creation. What if God chose to undo all that—to allow the canvas to be destroyed? What would it look like? Nothing short of chaos … and the extinguishing of all the light that is light.

I looked on the mountains, and lo, they were quaking,

and all the hills moved to and fro.

No more stability! The ground is shifting. I believe I preached about that a few weeks ago.

I looked, and lo, there was no one at all,

and all the birds of the air had fled.

I find that last image absolutely terrifying. Notice that the prophet is reflecting on what would happen if God systematically dismantled each and every day of creation: the heavens, the light, the earth, the animals, the people.

I looked, and lo, the fruitful land was a desert,

and all its cities were laid in ruins

before the Lord, before his fierce anger.

We have made such a mess of this world. How do we not deserve to have it all taken away from us?

And this is where we get to one of the real puzzles of faith. For God to be relatable to us, God must have emotions, right? So what happens when God gets angry? We have lots of Bible stories about this, and they’re always scary. But how much of this is simply our perception? How much is actual? When we speak of God’s anger, does the metaphor limit our understanding? Do we really believe that God wants us to cower in terror, like a child whose drunken father has just stumbled through the door?

When horrible things happen in the world, we might well wonder whether this is God’s doing—God’s punishment for the ways we treat each other. That’s a normal, very human feeling—it means we are able feel empathy and remorse on a large scale.

For Jeremiah, the Babylonian invasion feels like the end of the world. We know the feeling. We feel like we’re in a collapsed mine from which there is no escape. We need room to breathe. So God sends wind. Then we take a big gulp of it—and find that we have to cough to get it out of our lungs! Jeremiah proclaims that because the nation of Judah has abused its own vulnerable people, it will now be destroyed by foreign invaders.

Does God do that—intervene on such a scale, causing such disaster and suffering and death, for some higher purpose? Without our knowledge or understanding, that feels … oppressive. And so we are left with a theological question for all times and places: How bad can it get and still get better? Will we ever see all this chaos as … worth it? Will we ever be able to breathe freely?

We’re still in the middle of the story of God’s universe, so we don’t have definitive answers. But alongside these tales of terror, we do have some significant promises. We have Isaiah’s story of turning swords into plowshares. We have Ezekiel’s story of dry bones springing back to life. We have Jonah’s story of the full repentance of our enemies, and Malachi’s story of the sun of righteousness rising with healing in its wings!

And today we hear from the First Letter to Timothy, written in Paul’s name. This is a profile of a forgiven sinner, a man who was cruel and shortsighted but eventually was shown a new way to live: “I received mercy because I had acted ignorantly in unbelief.”

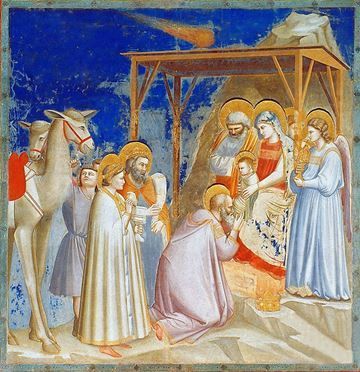

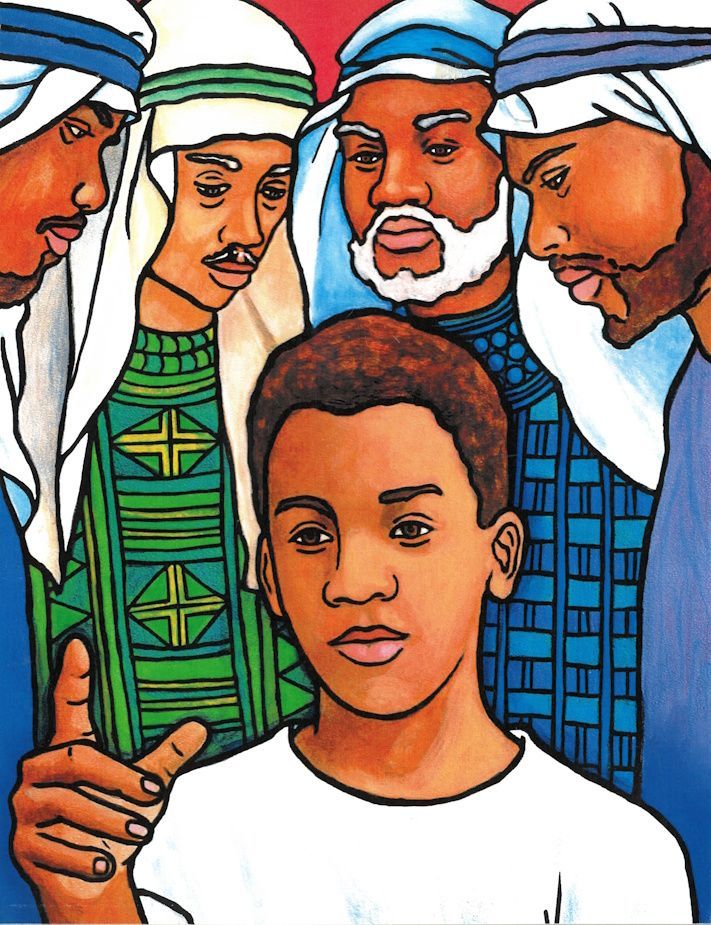

Listen also to Jesus’ parables. A lost sheep. What does a lost sheep have to do to get saved? And a lost coin. How does a lost coin get saved? What are its qualifications? Does it … believe really hard that it can be saved? How can a coin or a sheep even do that?

So, then, what about the “tax collectors and sinners” that Jesus hangs out with? The tax collectors are traitors to their people. They extort money for the brutal oppressors and enrich themselves in the process. People still do such things, you know. Sometimes they get elected. Sometimes they wear masks so they can’t be identified. Sometimes they stockpile guns and prepare for war. What if they don’t change? What will they do to get saved?

You want them to change, don’t you? To repent. To turn around. But the sheep never turned around. The coin didn’t bounce back out from under the dresser. Somehow the sheep and the coin got found anyway—rescued!

Do “tax collectors and sinners” deserve mercy?

Well, why did Paul receive mercy? Was it because Paul deserved mercy? Of course not. Nobody ever deserves mercy—that’s the point. Paul received mercy because he needed it. Because it was the only way to pierce the ignorance of his cruelty and finally give him some breathing room! Doubtless that revelation felt at first like a blast of Death Valley air. (Or Valley of the Shadow of Death!) But that’s exactly the place where the Good Shepherd finds us. He leads us out of the enclosed space and into green pastures, so that we may lie down beside still waters.

When you become a Christian, you have to expect to find horrible people being rescued from their dead-end lives. Indeed, without this possibility, our faith is useless. When you become a Christian, you have to be ready to see mercy in action—and to grant mercy yourself. If you can’t stomach undeserving people getting good things, there’s not much point checking out the Jesus movement. Don’t bother. You won’t find moral purity in the church, no matter how hard you look.

Now, that’s not to say we don’t pursue and pray for justice. We do! But justice for one person might not look the same as justice for another. Human beings tend to be terrible at doing justice to justice. We think that everybody we oppose should get what we think they deserve. Then, when we learn of our own ignorance, we believe that we ourselves should be shown mercy.

For God, justice first means giving people breathing room. The wind may blow hot at first, in the form of the consequences of our actions. But at least we are no longer trapped. There is a future on on the other side of drastic change. There is even a future on the other side of death! Ultimately, God folds justice and mercy together into a single reality.

Are you having trouble breathing today … like someone is kneeling on your neck? Here in the church, I pray you will find space to breathe—even if that breath comes at first like a hot wind, sweeping across the desert of your soul. Here, together, we follow the Good Shepherd out of enclosed spaces.

I pray today that the Church of the Good Shepherd can live up to its name—that those of us who find shelter here may no longer be in want, but find that we have been given everything we need. Including a whole pasture full of mercy, given by God and distributed by all of us to one another. Amen.