Alternate Shepherds

Jesus urges his own leaders to look back to the prophet Ezekiel and humbly place themselves into his narrative.

2025-28

sermon preached at Church of the Good Shepherd, Federal Way, WA

www.goodshepherdfw.org

by the Rev. Josh Hosler, Rector

The Fourth Sunday of Easter, May 11, 2025

Acts 9:36-43 ;

Psalm 23 ;

Revelation 7:9-17 ;

John 10:22-30

In the little town of Quepos, Costa Rica, there’s a coffee shop called Caffetto. Their logo is of a sloth embracing a warm cup of coffee, with a caption in English: “Because Adulting Is Hard.”

This is a popular saying among Gen-Z folks, and it’s true. Adulting can be very hard. It’s good to get as much guidance in the effort as possible. Today is Mother’s Day, and how many of us either still rely on our mothers for advice and support, or at least wish we could? Parents are responsible for making sure their children know that there is a place for them in this world, and for helping carve out such a place when the world itself doesn’t want to cooperate. Parents are supposed to be good shepherds.

On our second day of classes at the Máximo Nivel language school in Quepos, Christy and I were hanging out at the school’s pool. (I know—rough life, right?) That morning we met young people from several countries; some were there to study Spanish, but most had come because Máximo Nivel also organizes volunteer opportunities. One of our housemates was a 19-year-old from Philadelphia; she was playing her guitar at the pool and singing original songs. Another, an American expat from Spain, had graduated early from high school and was traveling Costa Rica on her own at the age of 17! There were young people from England and Switzerland, and a Colombian-born German. And then there were three young women from Queens whom we came to know as las chicas de Nuevayol. (You might only get the full reference if you’re a fan of Puerto Rican musician Bad Bunny.)

As we got to know all these young folks, it came out that I’m a priest. That didn’t take long; everyone always asks, “What do you do?” And two of las chicas were especially intrigued. They’d never heard of the Episcopal Church before, though when we mentioned Bishop Mariann Budde, they got excited: “Oh yeah! We saw what happened at the National Cathedral after the inauguration—she’s one of yours?” They asked us for more information: books, podcasts, articles ... anything about this branch of Christianity that they knew nothing about.

One week later over lunch, they said, “The reason we’ve been so curious about your church is that we’re gay. And we’re a couple. When we came out to our families, they weren’t helpful. And we know that we can’t possibly come out at our church back home … but we have so many good friendships there! This has become a crisis for us. Just before we came to Costa Rica, we were praying together, and we said, ‘God, please help us. We don’t know what to do. We love our families and our church, but we are in love, and we need to be who you made us to be. We can’t keep hiding like this. Please send someone to guide us!’ And now … here you are.”

When the ones who are supposed to be good shepherds aren’t doing their job, it’s natural to seek out alternate shepherds. And the dilemma these two young women are facing is indicative of the most obvious fault line dividing Christians from one another in the world today. Yes, it’s partly about the Bible and how to interpret both its contents and the nature of its authority. But it’s also about how willing we are to humble ourselves and learn about what we don’t yet understand. When fault lines develop this clearly within a religion, it may well lead to a major, permanent division—like we heard about in today’s gospel.

This passage could benefit from a whole bunch of footnotes. We could put an asterisk after “the Jews” to remind ourselves that Jesus is also a Jew. If I were to insist that las chicas’ church in New York isn’t Christian, simply because we disagree on theological matters, that would be both dishonest and unfair. In the same way, it’s not helpful for the gospel writer to imply that “the Jews” are the problem here.

We could also put an asterisk after the phrase “my sheep hear my voice,” and point ourselves back to the prophet Ezekiel, chapter 34. If I had time, I’d read you that whole chapter, because it’s all about sheep and shepherds. Ezekiel, speaking with God’s voice, criticizes the “shepherds of Israel”—that is, his own religious leaders at the time of the Babylonian exile—for enjoying the benefits of privilege while persecuting the people they were supposed to be protecting.

God promises to rescue the sheep from these bad shepherds. The sheep will also be judged, God says, because the strong sheep have been victimizing the weaker ones; this is where we first hear about separating “the sheep and the goats.” And we hear: “I will set up over them one shepherd, my servant David, and he shall feed them: he shall feed them and be their shepherd.”

Understand that when Ezekiel writes, King David has been dead for centuries. Ezekiel means that though the line of kingship in Israel has been broken by invasion and exile, God will restore that kingship and will put a descendant of David on the throne of the chosen people. This came to be understood as a prophecy about the coming Messiah.

So we could also put an asterisk after the phrase, “If you are the Messiah” and talk about the lack of theological consensus among ancient Jews. Jesus is saying, “What if your assumptions are wrong about what the Messiah is supposed to be like? Does that need to divide us? But you have allowed yourselves to become the bad shepherds. And I am the descendant of David that Ezekiel spoke of.”

He might as well pull out a guitar and launch into a Bob Dylan song:

Come mothers and fathers throughout the land

And don't criticize what you can't understand

Your sons and your daughters are beyond your command

Your old road is rapidly agin'

Please get out of the new one if you can't lend your hand

For the times, they are a-changin'

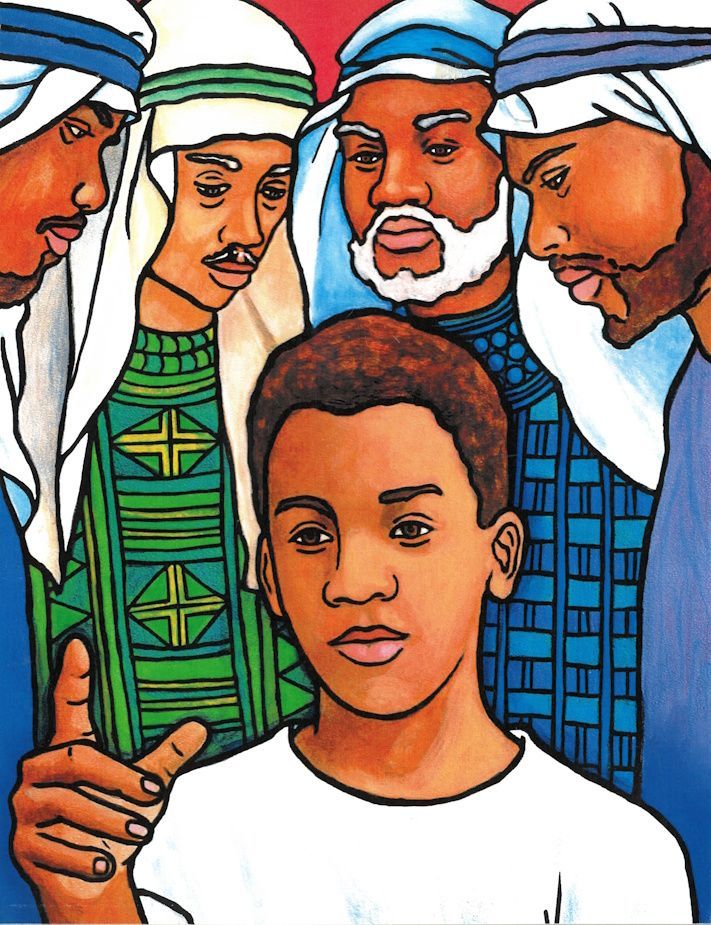

Put a big fat asterisk as well, then, after the phrase, “You do not belong to my sheep.” Jesus is not creating a dividing line, but acknowledging one that already exists. He urges his own leaders to look back to the prophet Ezekiel and humbly place themselves into his narrative: “You think you’re shepherding our people faithfully, but you’re not. You are failing to meet their needs in this specific moment in our history. God has sent me to call you to account.”

But passages like this did indeed lead to a far worse, permanent division, and that has been nothing but tragic. In the fourth century, when Christianity became a tool of the empire, it gained enough power to persecute Jews, and it has continued to do so over and over throughout history, using gospel passages like these as justification for its atrocities. Even many of our revered saints, like John of Chrysostom and Martin Luther, inspired pogroms with their hateful words. And we all know what happened in Germany in the 1930s and ’40s, when the people chose to elect bad shepherds into office.

You can’t follow the Good Shepherd and persecute others—no matter their religion, no matter their immigration status, no matter their sexual orientation or gender identity … no matter how much you may disagree with them. The bad shepherds are those who would place limits on God’s love. The bad shepherds act in bad faith, out of their own fear of change. They fail to hear God’s voice saying, “See! I am doing a new thing.”

In my own weaker moments, I, too, can be a bad shepherd and need Jesus to call me to account. If I declare that reconciliation across a dividing line is not possible, I’m limiting the power of the Holy Spirit. Well, today I’m not condemning anyone. I only ask … are the shepherds of our faith being humble, learning from what God is doing? Are the shepherds able to see healthy love right in front of their faces, and rise above their old prejudices about what love is allowed to look like? Or will they tell the sheep, “You don’t belong here”?

So who doesn’t belong in the sheepfold of God’s world? Not those who disagree about the messianic status of Jesus. The only ones who don’t belong are those who see obviously good works being done and say, “No, these works are bad and cannot be of God.” Coming to belong again simply means learning humbly and changing our minds. So whether or not you believe Jesus is the Messiah, the prophet Ezekiel tells us that what matters is how you handle your responsibility as a shepherd, and as a fellow sheep, in the one sheepfold of all of God’s creation.

Las chicas just got back to New York and, I understand, returned to their home church this morning. I have been praying for them all weekend. We have found a couple Episcopal churches to send them to, led by priests we know and trust. But who knows? They may not find a home in the Episcopal Church. They may stay in their own church and work on changing it from the inside. Or they may find good shepherds in a place none of us has yet imagined.

Christy and I thought we were going to Costa Rica to get better at Spanish, and we did—but God had bigger plans. We were called to be shepherds, not just for las chicas, but also for several others of the young people we met. We shared conversations about relationships with parents … about college and career uncertainties … and about what it’s like to experience the presence of God. We got to accompany a 19-year-old woman from England to her first church service ever! And a young man told us over lunch one day, “I had never really thought about God until I came to Costa Rica.”

There’s something about travel that opens us up to God’s creation in new ways, and often that happens through unexpected new friendships. All these young friends have been in my prayers since we returned from Costa Rica more than two months ago. What a blessing and a terror it is to be a young adult in today’s world—to be growing into a deeper knowledge of yourself, and to be asking, “Who are my mentors? How do I know I can trust them? Who will allow me to be the person God made me to be—the person I continue to become? Who will hold out a space for me to step into as I engage in this difficult practice of adulting? As I listen for the voice of the Good Shepherd, who will be good shepherds to me? And then, to whom will I also become a good shepherd?”