Up the Mountain Together

Over time, these stories will become your own stories. So keep coming back to them.

2026-14

sermon preached at Church of the Good Shepherd, Federal Way, WA

www.goodshepherdfw.org

by the Rev. Josh Hosler, Rector

The Last Sunday after the Epiphany, February 15, 2026

Exodus 24:12-18 ; Psalm 2 ; 2 Peter 1:16-21 ; Matthew 17:1-9

The Second Letter of Peter was likely the final piece of the Bible to be written, probably in the early second century. So it was not written by Peter himself, but by a later community that sought to revere him by attending to his teachings.

How do we know this? For one thing, the author speaks of the letters of Paul as if they were holy Scripture—something Peter could not have said in his own lifetime. For another, the letter responds to anxiety that long after Jesus’ death and resurrection, the world went on as always. The author of this letter, using Peter’s voice, counsels the community to hang in there and wait patiently for Jesus to return and renew the entire world.

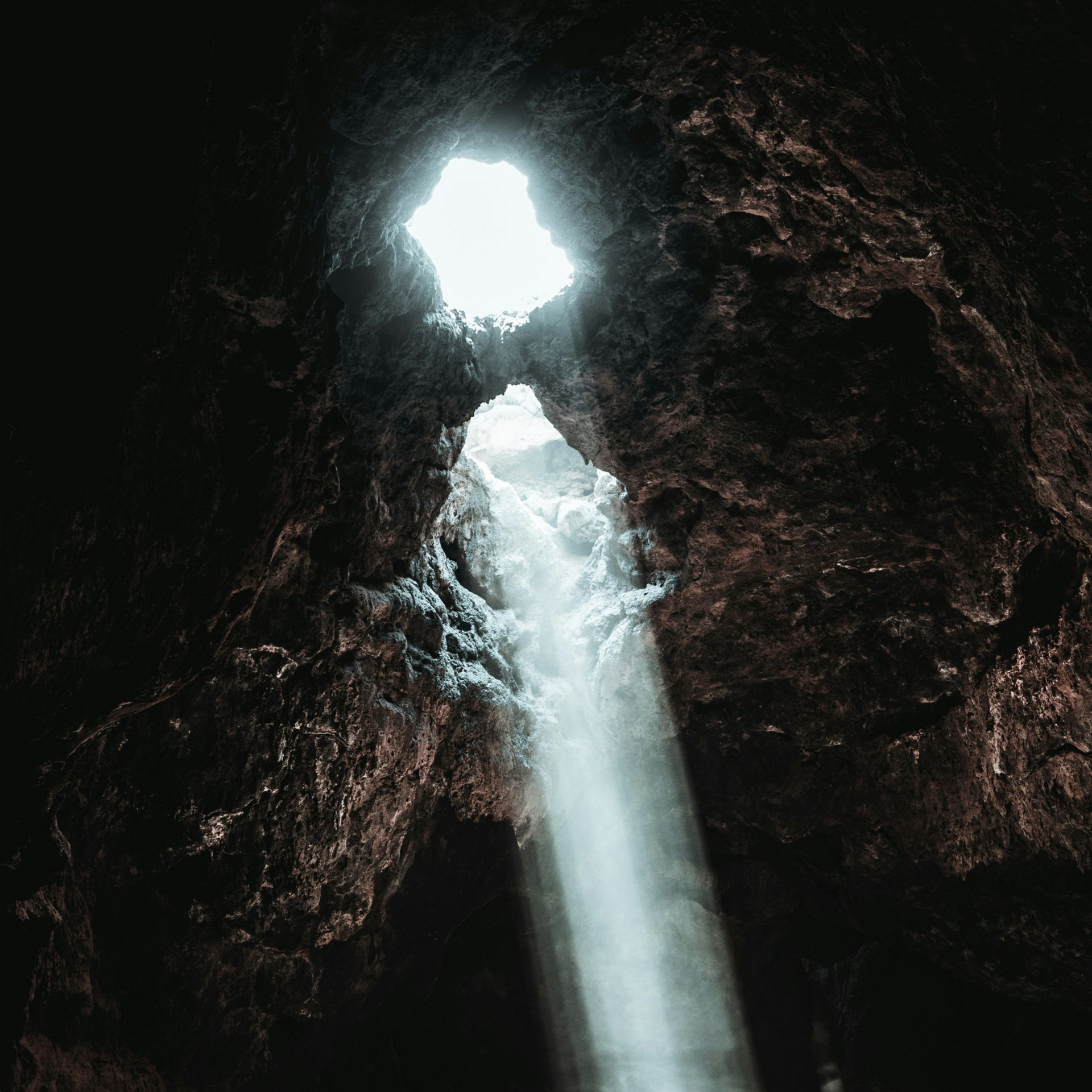

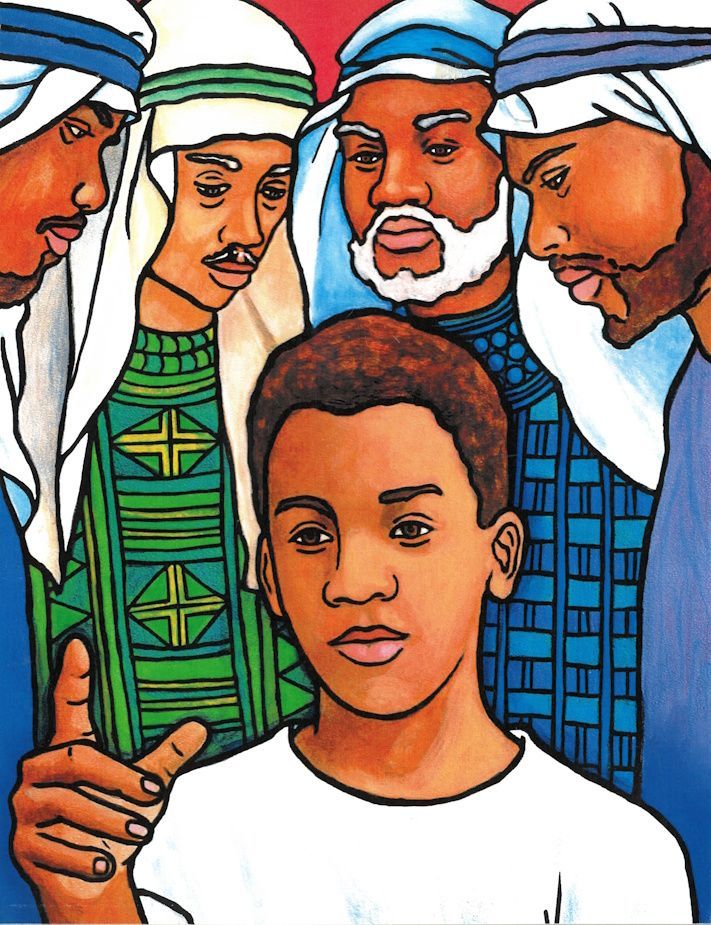

In today’s passage, he urges his community to keep coming back to the story of the Transfiguration of Jesus on the mountaintop. He writes, “You will do well to be attentive to this as to a lamp shining in a dark place, until the day dawns and the morning star rises in your hearts.” In other words: “Look! Here is just enough light to carry you through the night until the sun returns. Though you were not yourself an eyewitness, you can trust the stories of those who were. Over time they will become your own stories—your own direct experience.”

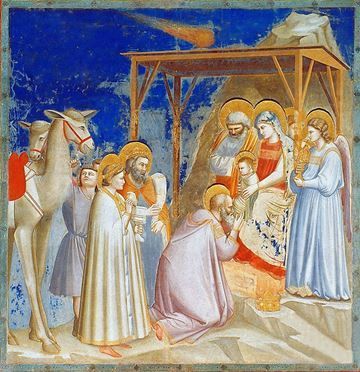

Every year on this particular Sunday, the Last Sunday after the Epiphany, we hear one of the three versions of the Transfiguration. If we show up to church on this day, it is the story that is presented to us—and we can spot resonances in the other chosen readings, from Moses on the mountaintop receiving the Law many centuries before Jesus, to the Second Letter of Peter, reflecting on the Transfiguration a century later. Scripture is talking to Scripture. Here are high mountaintops and amazing shows of light and ancient role models returning to guide us onward!

You know, if you grew up as a Christian, someone probably advised you when you were young to read your Bible. Yet most Christians have never read more than bits and pieces of it, because much of it is rather difficult to relate to without lots of context. But let’s say you have read the entire Bible once, straight though. Haven’t you “got it” now? Isn’t it like reading a really long, challenging novel and then setting it aside to start a new one?

Well, the Bible isn’t that kind of book. First, it’s not a single book, but an entire library. It’s not intended to be read from cover to cover like a novel—though certain portions of it are quite novelistic. It’s not intended to be read randomly, like flipping through a book of poetry—though much of it is indeed poetic and can be approached in this way.

The Bible isn’t even supposed to be read silently to yourself! There are many benefits to doing so, and of course I encourage the practice. I’m just saying that it wasn’t written with silent reading in mind. Throughout the centuries in which it was being compiled, most of the people who were to make use of it were illiterate.

Instead, the Bible is intended to be proclaimed in community, out loud—and then unpacked and applied in the living of our lives, both in community and as individuals. If you hadn’t been here today, the Transfiguration of Jesus would not have been presented to you. You might have happened to choose to read it in the privacy of your home, but how likely is that? And how could you have drawn the obvious connections to these other passages?

Look at the Exodus passage: “The glory of the LORD settled on Mount Sinai, and the cloud covered it for six days; on the seventh day [the LORD] called to Moses out of the cloud.”

Compare this to the gospel reading: “Six days later, Jesus took with him Peter and James and his brother John and led them up a high mountain …”

What’s going on here? Is this a literary device? Or did Jesus literally take them up the mountain “six days later”? Six days after what? In Matthew and Mark, the Transfiguration happens six days after Peter says out loud that he believes Jesus to be the Messiah. In Luke, however, it’s “about eight days” later.

Would you have noticed this if you were reading the passage to yourself at home? Or would you have blown through “six days later” without paying any attention to it? What is the significance of it? What could it possibly have to do with my life, as I come to be with this community on the first day of the seven-day week? And why does Luke tell it differently? Let’s wonder about this together.

Do you see? It’s one thing to control our own reading of the Bible. It is quite another to hear it read out loud on a regular schedule, and not to be able to control which stories are placed into our ears today.

In short, the Bible is best approached on many occasions, over time, with other people. And everything in it was carefully selected not necessarily because it was journalistically factual, but because for ancient Jews and for early Christian communities, it was useful. It was doing something noticeable. It was changing the way people lived.

Now, you all know that I’m big on the ideal of people making it to church every single week. Hopefully I don’t shame anyone for not doing so, but only keep encouraging it based on my own experience. If I have to miss church one week, I really, really feel it. It means I’ve missed out on whatever slices of this divine proclamation were served up for us today. I have missed a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to hear the Bible in this way, at this time, with these people.

The other piece that’s really important, of course, is that the Bible is so, so contextual. We can read the words and believe we understand them. But coming together in community to share these words gives us far more opportunities for better understanding.

Here’s another example. What do you know about the Epicureans? They were an ancient Greek school of materialist philosophy with a shockingly advanced understanding of physics. But when they applied their theories to the question, “How should we live our lives?”, they arrived at a conclusion summarized in a poem by Philodemos in the 1st century BCE:

Don't fear God,

Don't worry about death;

What is good is easy to get;

What is terrible is easy to endure.[1]

To summarize, the Epicureans believed that the gods don’t really interact with human beings—that there is no afterlife—that the main point is to live a life of pleasure—and that all suffering is bearable because we know it will eventually end.

Now, by the time of the Second Letter of Peter, Christianity was an established movement, though it still thrived largely outside the public eye. Epicureanism was one philosophy competing with Christianity by promoting a life of easy, individualistic pleasure instead of sacrificial commitment. (That’s an oversimplification, but this is a sermon, not an academic paper.)

My point is that the Second Letter of Peter may be written in opposition to the Epicureans—and maybe also against other competing groups, like the Stoics and the Gnostics and the Antinomians, and you can learn more about them on Wikipedia. All these schools of thought were popular because, each in their own way, they made sense to people.

But this author writes them off as those who follow “cleverly devised myths.” By contrast, he tells his community, “You know that we’ve got the right story here, because Peter saw the Transfiguration of Jesus with his own eyes, and we’ve preserved his story for all future generations. We know that Jesus was speaking directly with Moses and Elijah, who had died centuries before. We know that the Voice of God spoke to us on the mountain and urged us to listen to Jesus. We know that Jesus went from here down the mountain toward Jerusalem to his death. And we know what happened after—that he returned to us again! These stories that were Peter’s stories have been transmitted to you, and now they are your stories as well.”

If that doesn’t satisfy you, I totally get it. The author seems to assume that no other school of thought is based on anyone’s personal experience, but is a mere deception based on some sort of plausible fabrication. It’s not a fair way to argue, and his detractors aren’t even in the same room with him. Who’s to say he’s not doing the same thing? These questions need not threaten your faith. If you’re asking them, you’re wrestling well.

All the same, life is long, difficult, and confusing, and annoyingly, it keeps changing. Trying to hold onto a good situation is like trying to hold onto running water. We never know what’s coming next, and we never feel prepared to meet it. Sometimes all we have to guide us through the confusion are other people’s experiences, handed down to us—the wisdom of our elders. It’s up to us to decide which elders we trust.

That’s what the author of the letter is doing here. He says, “Don’t listen to know-it-alls who gather all sorts of facts but have no wisdom to apply them. Allow that you don’t know it all. Allow that life is confusing. Allow that you can’t do this on your own. Hold onto these ancient words, and keep coming back to them. They will help you deal with the future—no matter where it leads!”

Eventually, to all of us comes a time to share our own wisdom with the next generations. Our life experiences are real because they are our own. Can we trust them to give us insight into the huge questions of life—insight that will also help those who follow us? To some degree, yes, because personal experiences are real data. But we always do well to hold them up against the experiences of those whose lives have been very different from ours. Diversity of belief is a strength, because together we arrive at a deeper understanding of truth than we do all on our own.

When we gather here on Sunday mornings, on what early Christians called the eighth day, we are going up the mountain together to experience the holiness of God—the fundamental truth of the personality behind the entire universe. Isn’t the view spectacular?

But if you don’t see it yet, hang in there. Keep journeying up the mountain with us. And keep setting your stories alongside our stories and alongside all the ancient, sacred stories. Amen.

[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Principal_Doctrines, retrieved 12 February 2026